Frames, doors, windows, shutters, and openings of all sort fill Yojimbo. Kurosawa practically shoves them in our faces and then interrupts them with bars, changes their shapes and sizes, opens and shuts them, moves actors in and out of them, and generally breaks them down. It's dizzying to try to keep track of all the variation on framing used in the movie.

As we watch the grates and windows and other frames in Yojimbo, we have to ask some questions. Are we looking inside or outside? Are we (i.e. the camera) situated in or out? Where are the actors in relation to these frames? Do we have a clear view through the frame or is it interrupted? What's happening on the other side? The movie is an endless contemplation on this theme, developing all sorts of variation on the themes of framing and viewpoint.

Let's see how Kurosawa does this, in just the first 15 minutes. The film opens with one man (Sanjuro) outside, by himself, in an open landscape. In a short prelude scene, a father and son appear fighting, still outside; the son runs off and the father speaks to Mom through an open door. Unremarkable so far, but it's our first framing. Mother is inside. Now we have two (Sanjuro and Dad) outside, with Mom inside. They are at three different planes: Sanjuro drinks from a well, Dad stands at the door, Mom weaves inside, but they are all aligned for us in one line. None of them are looking at each other. Suddenly, our perspective switches, and we are inside, looking at, past Mom, to Dad and Sanjuro. Then we are back out; Dad goes in, castigates Sanjuro, and slams the door shut. End the prelude. Not much, but it hints at how Kurosawa will play with frames.

As Sanjuro goes into the village, we are with him outside at first. We see a few men looking out through a square opening. Then a few men looking out through a barred opening, then a few women peering out through a different barred window, then a second group of women. Shortly, Hansuke, the little constable, comes walking out through a door. Then a large gang emerges from a larger, squarish door. After the confrontation, Gonji pops his head out of a little square door. Each time, Kurosawa adds a little variation on what we've seen before. So far, we and Sanjuro have stayed outside.

We go inside with Sanjuro, and Gonji (the Old Man) angrily shuts Hansuke out. So, we are "inside," and others are "outside." But the shack is filled with cracks and gaps and openings; a little later, even these will be opened up. Kurosawa plays with this a little more. We are inside, but abruptly we see Gonji peering out, from a second room (a kitchen) through a wide horizontal pass-through, into the first room. The two rooms are partially separated by hanging beaded cords; the whole place is filled with slots, grates, and other "semi-dividers." The hammering sound of the casket-maker, unseen but nearby, penetrates the flimsy walls.

The variations build. The two walk from room to room. In the kitchen, looking over the two men's shoulders, we see four men outside, through a square window. Okay, 2 inside looking at 4 outside. But then, the camera pans back and surprisingly the casket-maker shares the same space, and he is peering out through his own window at the same four men, in a brief triangular composition. The pan continues moving, now focusing on Sanjuro and Gonji, peering out from a different window at the outsiders as they walk along.

And it continues. Returning to the first room, Gonji throws open one big shutter, then another, then a third. Our whole notion of where we are, out definition of 'in' and 'out' seems subject to change. But when he opens the shutters, bars obstruct our view. Throughout the movie, our views through openings are frequently interrupted by bars and grates. Windows appear out of walls; openings are slammed shut; walls are translucent - glowing from the inside out So, Kurosawa constantly breaks down the distinction between one side of the frame and the other.

All the foregoing variation on framing, perspective, and participants has taken place in just the first fifteen minutes.

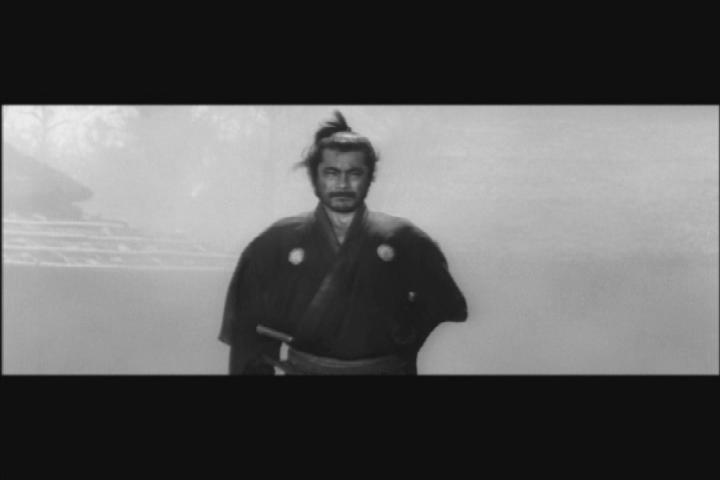

Two more aspects of the movie work with this "theme of the frame." First, Sanjuro is omnipresent; he participates in or observes every scene. Yojimbo means 'bodyguard,' and in this nameless, gang-dominated little Japanese village, bodyguards are in great demand. Enter Toshiro Mifune, who calls himself "Sanjuro Kuwabatake," a nonsense name, literally translated as 'thirty-year old mulberry field.' We know nothing about the events of Yojimbo, other than what Sanjuro sees, does, and creates.

He is once called the "author" of a certain action, and another time sits high above the action in something like a director's chair. Second, the use of the telephoto lens compresses the planes of action. Everything (foreground, middle distance, and background) is in equally sharp focus, so outside and inside seem almost squished together.

So, it's very much like Sanjuro is making the movie, as if Sanjuro is Kurosawa. He authors and directs the action. The film consists exclusively of stuff he sees. And there are all these "frames" in his view; what's happening on the 'other' side of the frame is constantly challenged. That is to say, we are forced to view the frame from inside and out, with fewer or more actors, with the frame interrupted and changing. All of this asks us to think about movie making and its choices.

Think about the screen that we see the movie or DVD on. It is a rectangle that encapsulates a scene of some action; what goes on inside that frame is Kurosawa's choice. And within the movie Yojimbo itself, we see other frames, with all the dynamics around those frames that I've described. Perhaps this "framing" does not mean anything, in some deep philosophical sense, but by erasing the distinctions between Sanjuro's frames, Kurosawa says something about own frame (i.e. the movie screen in front of us). It's fairly simple, and aspirational. The movie-maker wants to draw the audience into the movie and also wants to put something out, to have some impact outside of the screen.

Yojimbo plays at a couple other levels. First and foremost, it's a samurai action film, with lots of swordplay and fights. Second, it's a social commentary on postwar Japanese capitalism and corruption. It's also very funny, whatever else might be going on, or not going on with it.

The article focuses on these few aspects of the film that I found interesting, and does not replace Wikipedia's excellent, encyclopedic article. Also, if you want a DVD, Yojimbo & Sanjuro - Two Films By Akira Kurosawa - Criterion Collection is excellent, including Stephen Prince's Commentary. He actually narrates/comments right over the entire 110 minutes of the film. Very worthwhile.

The action, the swordplay, and the fighting, speak for themselves. It's an exciting movie, well-filmed and well-choreographed. The music in this 1961 production, unsurprisingly, sounds like "beatnik music." Like most Kurosawa films, each player has his own theme music. The confined, choreographed gang fights reminded me of "West Side Story," but as that film also came out in 1961, the resemblance is coincidental. (Could Kurosawa have seen the earlier Broadway stage production?)

Befitting an action picture, Yojimbo was filmed in a very wide-screen format, an aspect ratio of 2.35 to 1:

This may not be the best image to demonstrate Kurosawa's brilliant use of the format, but if you can, you want to see Yojimbo on a DVD that preserves the full, wide-screen view.

Yojimbo looks and feels like an American Western. While it was later re-made by Sergio Leone as the first 'spaghetti Western,' starring Clint Eastwood, Yojimbo itself is a fairly obvious Western, set in 19th Century Japan: the dusty street of the town, the shuttered windows, the face-off between the lone good guy and the bad guys, the wind-blown leaves and dust, etc. etc. Some people say that, in response to criticism that he was too Westernized in his film-making, Kurosawa decided to go all out, and essentially parody his critics.

Power in the village lies with two wealthy men, a silk merchant and a sake brewer. Symbolizing Japan's capitalists, they mostly operate behind the scenes, and we don't see too much of them. They operate through their respective gangsters, Ushitora and Seibei, just as the postwar Japanese capitalists did. Equally corrupt and reprehensible are the government officials, shown as a local constable and as "an inspector from Edo." You'll see that only the inspector and Takeumon the merchant ride in covered chairs (palanquins), demonstrating their wealth. Ushitora and Sambei, with their heavily armed gangs, cower before the men of real influence.

In the postwar era, the traditional relationships of Japanese society were becoming frayed and distorted. Traditional Bushido defined five moral relationships: Master-Servant, Father-Son, Husband-Wife, Older-Younger Brother, and Friend-Friend. The fouled-up relationships between the merchants, the gangsters, and the gangsters' families show just how fouled-up Japanese society was (or how fouled-up Kurosawa made it out to be). There's a wonderful scene where Sanjuro and Seibei sit down for the first time, to introduce themselves and talk. Unceremoniously, even scandalously, Seibei's wife barges in and tells him "We gotta talk." What a distortion of the traditional, proper Husband-Wife relationship.

It's fun to see the actors in Yojimbo and the roles they have had in other films. Toshiro Mifune and Takashi Shimura worked with Kurosawa on many other movies. Tatsuya Nakadai, who played the poisonous young Unosuke, twenty years later appeared as the Lear-figure in Kurosawa's Ran. Isuzu Yamada, who had played Asaji (i.e. Lady Macbeth) in Throne of Blood, appeared in Yojimbo as Seibei's wife, another behind-the-scenes, deadly conniver. Yoshio Tsuchiya, who (as Rikichi) had lost his wife in Seven Samurai, once again lost his wife in Yojimbo. And Daisuke Kato, as the comic half-wit villian, Inokichi, had played one of the Seven Samurai.

There's also a scene where Sanjuro (Toshiro Mifune) and Master Homma (Susumu Fujita) meet. Homma says that Sanjuro has replaced him, earning 50 ryo to his 2. In real life the actor Mifune had, in fact, replaced Fujita as a highly paid leading man, a small, self-refential joke about movie-making.