Ikiru, directed by Akira Kurosawa, aka “To Live”

What does it mean to live? The protagonist of Ikiru, Kanji Watanabe, a worn-down Japanese civil servant, we are told at the start has hardly been alive for the past thirty years. He has justly earned his office nickname, “The Mummy.” The opening frame shows a X-ray of his stomach, and we are promptly informed that he has terminal stomach cancer. So, in light of his imminent death, Watanabe’s life is immediately put forth for our examination.

It stars Takashi Shimura, an actor who starred in many of Kurosawa’s early films, and features many of Kurosawa’s regulars: Kamatari Fujiwara, Nobuo Nakamura, Minoru Chiaki, Bokuzen Hidari, Atsushi Watanabe, and Eiko Miyoshi. Interestingly, it was the only Kurosawa film made between 1948 and 1965 to not include Toshiro Mifune. Ikiru has been included on many lists of the “Greatest Movies of All Time.”

This article focuses on certain aspects of the film, and does not replace Wikipedia’s excellent, encyclopedic article. Also, if you want a DVD, the Ikiru – Criterion Collection is excellent, including Stephen Prince’s Commentary. He actually narrates/comments right over the entire 143 minutes of the film. Very worthwhile. (You can turn the commentary on or off.)

Four Parts of the Film

- His Old Life

- Living for the Moment

- Living through Another

- His New Life

His Old Life

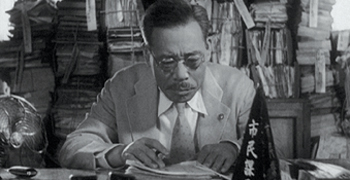

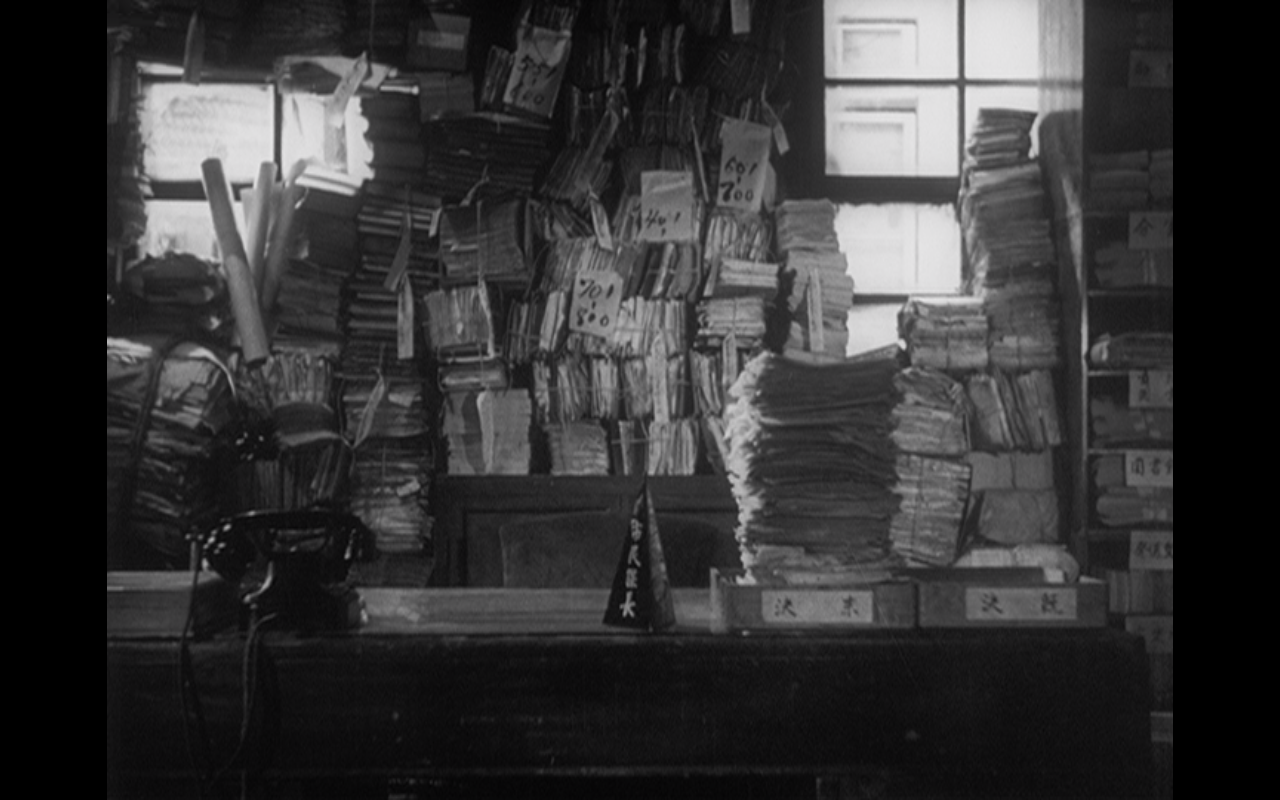

Here in the first part, we see, and we experience the deadening effect of Watanabe’s existence as a mid-level bureaucrat in Japan’s civil service. He is a section head in the Public Affairs division, responsible for nothing except shuffling papers and passing the buck. Mountains of papers literally overwhelm him and his staff; it’s a dark, dusty, stultifying place. A group of poor women come to his department to complain about an open sewage pit in their neighborhood, which they would like filled in and the site made into a children’s playground. They are shuffled from one office to the next, by one bureaucrat and another, in a hilarious series of wipes (the side-to-side transitions favored by Kuroswawa) until they end up right back where they started, at Public Affairs.

Meanwhile, Watanabe has visited the doctor, and while the doctor deliberately conceals the real diagnosis (per conventional Japanese medical practice at the time), our protagonist figures out the truth, comically assisted by another patient graphically describing the symptoms of stomach cancer.

We’re also introduced to Watanabe’s home life; his adult son and daughter-in-law live with him. Between these scenes and some flashbacks, Watanabe’s estrangement from his son is made clear. Watanabe has tried to do the right thing for his son, refrained from re-marrying after his wife’s death, and endued a soul-crushing job, but in a number of ways, he had not been there for Mitsuo (his son) at critical moments. It’s a sad situatation, and now the son and his wife are more concerned with getting ahold of Watanabe’s retirement money than for the man himself.

Living for the Moment

Watanabe uncharacteristically, surprisingly, even shockingly, stops showing up at the office. His co-workers and his family are mystified. Time in Ikiru, is quite fluid and unpredictable. Events that seem to happen on the same day might actually occur several days apart. In one scene the characters comment on how cold it is (presumably winter), and in the next, there is a heat wave (summer). It can take 2-3 viewings, or a few rewinds of the DVD to get an accurate sense of time.

With much of the film, we learn a lot by inference, not by seeing things explicitly. In the hospital, an intern and a nurse debated what they would do if they knew they themselves had a terminal disease like stomach cancer. The nurse pointedly noted that she knew where the bottle of sleeping pills was. Not much later, in the bar, Watanabe produces a bottle of sleeping pills, which he says he has no use for. The inference is clear: he had considered suicide (seriously enough to get the barbituates), but had rejected that course.

After determining his actual condition, Watanabe draws out a large sum of money, and apparently resolves to have fun spending it. But, as he admits to a writer who he meets in a bar, he doesn’t know how. Upon hearing his story and learning his fatal condition, the writer agrees to show him a night on the town.

The two of them go to a pachinko parlor (similar to slot machines), a dance hall, another bar, another vastly crowded dance hall, and so on. Lights flash, music plays, and there’s constant noise. They drink together, they go to a striptease show. The evening ends with the two of them in a cab with two distinctly unappealing prostitutes (one of whom peels off her false eyelashes). Overall, it is a grotesque scene, and is Kurosawa’s indictment of hedonism in general and Western influence on postwar Japan in particular.

Two things to watch for in the ‘Night on the Town’ scenes: One is his hat. A girl in a bar mischievously runs off with his old hat, and the writer persuades him to buy a new one. He does so, and the crisply fashionable new hat becomes the symbol of the new man (see photos below). That’s one thing I like about Kurosawa; he usually explains his symbolism. How do I know that the hat symbolizes the new man? Because one of the characters tells us so! The second thing to watch for is Watanabe singing “Life is Brief.” Really touching.

Living Through Another

Ikiru shows us how Watanabe has lived conventionally; that life has proven unsatisfactory. Then he tries to live for himself, “Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we may die.” Kurosawa practically hits us over the head with the notion that that is not a good answer either. So the movie explores these different options for living. Indeed, the Japanese word “ikiru” means “to live,” or rather something like “to live a meaningful life.”

In this third part, Watanabe encounters a young woman from his office, who (in a tellingly comic indictment of the civil service bureaucracy) needs her boss’s signature to quit her job. He is struck by her liveliness and zest for life, and begins to take her around, including the pachinko parlor and other spots that he was recently introduced too. As far as we’re told, and as far as we’re led to believe, he is not pursuing the young woman sexually, although his family is convinced otherwise. The young woman, Toyo, reaches the same conclusion and pushes back, “Why are you following me around? Keep your old man’s infatuation.”

Toyo’s pushback, as I call it, takes place in a cleverly filmed scene in a multi-level restaurant. Toyo and Watanabe sit a table. Behind them, through a glass window, in the next room (and in another world), well-dressed, wealthy teenagers are preparing a big birthday party. And, briefly, in front of our two, we see another couple, also well-dressed, upper class people. Toyo (who now works in a sweatshop-type factory, making toy rabbits and who has holes in her stockings) will never be part of their world. Kurosawa interweaves this kind of social commentary, or perhaps, he makes such social commentary an integral part of what it means “to live.”

As the youngsters in the background laugh and enjoy themselves, Watanabe tries to spit out his motives. It’s difficult for him, because he almost certainly doesn’t fully understand them himself. In a scene that practically terrifies young Toyo, he tries to explain how her sheer vitality makes him feel alive, almost vicariously. She tries to explain that her life is nothing, all she does is work and sleep. (She neglects to mention that she also eats, although we are treated to seeing her continuously stuffing herself with all kinds of food and drink. Another contrast with Watanabe’s near-lifeless lack of appetite.) In a fit of exasperation, she thrusts at him one of the silly little white rabbits that she assembles, explaining that at least she makes something, that she feels close to all the children who play with the toys.

She challenges him to make something. “No, no,” he replies, “Not in that office. I could never make anything.” But then, he has an epiphany. His eyes light up; he seizes the little rabbit and leaves their table. As he heads down the stairs, the teenage birthday girl herself is coming up. Her friends sing “Happy Birthday To You,” (in English!) and the two of them cross paths.

But of course, it is also Watanabe’s birthday, in a very real sense. At that moment, on that day, he came alive. He was born. (A point which Kurosawa underscores for us a little later on, when, at another critical moment, strains of “Happy Birthday” are heard again in the soundtrack.)

His New Life

The narrative of Ikiru takes a sharp turn here. Watanabe proceeds to his office, dusts off the proposal for the new park, and suddenly informs his co-workers that they are going to make it happen. He orders one subordinate to prepare a full report that same day, while he and a couple others will go to inspect the site. With amazed bureacrats in his trail, he strides out the doors. A siren wails, louder and louder, and then the scene fades to black, and the narrator informs us that our protagonist has died. Five months have elapsed since “the day,” and we see Watanabe’s formal wake.

(I’m tempted to get into Christian allegories of life, death, and re-birth. But I won’t. Kurosawa was not a Christian, and as far as I can tell, was distinctly lukewarm about Western influences on postwar Japan. But, someone else might be able to make more of the religious aspect than I will. I don’t know if Buddhism or Shintoism have comparable perspectives.)

This last part of the film, about one-third of the running time, is told is an entertaining and thought-provoking way. It takes places at his wake, and this segment consists of flashbacks, all framed by the wake, in this way, somewhat resembling Rashomon‘s narrative style. Indeed, as in the more famous movie, truth is a little hard to get at. “Who did it?” is the question. Although in Ikiru, the “who did it?” applies to “who really built the park?” as opposed to “who committed the crime?” And, by the end of Ikiru, we know for a certainty who was responsible for the park – Watanabe. Although, in keeping with the film’s inferential tone, we never see any explicit decision or announcement, such as “Yes, we will build the park.” Nor do we ever see any of the bureacrats that Watanabe pesters give in and tell him “Okay, my department will approve this.”

But it’s a delightful scene, if any wake can be delightful, to see the big bureacrats spout their cliches, and, after they leave, and the sake flows liberally, as one person and another talks, slowly, the truth of Watanabe’s efforts come out. It is during the wake itself, the wake-flashbacks, and the building of the park, that Watanabe’s relationship with the poor women of the neighborhood becomes clear: he’s the one who finally does something for them, and their appreciation is real and touching.

The last flashback, is told by a policeman, who saw Watanabe, in the park, in his park, on the night he died. It’s a marvelous scene, and a fitting end to a marvelous movie.